“How does one represent his own time?…

Surely not in attempting to illustrate it, nor by commentating on it or following it. In any case, it remains opaque to itself and to us. “We don’t see anything there!”, to repeat the lofty expression of critic Daniel Asasse, the man who taught us how to look at the details, and even beyond them. We attempt to see clearly, to enter into our own time—not with our eyes closed, or our vision obscured by an oversaturation of images, but with eyes wide open to occurrences that might amaze, even surprise, us. There are blind spots in our own time and we do not know how to recognize them or draw them out of their eloquent obscurity. Deafening silence. No words, no faces, no works… or rather, fittingly, there are indeed creative works that speak to us, captivating us and shedding illumination on our time. One example is seen through the eyes of Houda Ghorbel and Wadi Mhiri in their new work “Ward et cartouches” (“Ward and Cartridges”).

I had the opportunity to meet them during the exhibition “Traces: Fragments of a Contemporary Tunisia,” presented at Mucem in two sections during 2015 and 2016. Even then, their video piece “Perles de famille” (“Family Pearls”) had captured something evasive and imperceptible, namely the fleeting memories tied to familial history. The aged images surfaced by a wave of the hand, revealing what was buried beneath. A tender gesture caresses each grain and brings us into a lost world that was all but demolished. We guard traces of it, traces lodged deep within ourselves and our history, and it necessitates a sensitive, attuned work of art in order to resurface something we had hoped to never lose. The seeds of our time, united with the images of the past—without a sense of nostalgia, but with fidelity to history—have a genealogy that has shaped us and keeps us standing.

“A work of art should always teach us that we have not seen that which we believe to see,” noted Paul Valéry. It is this side-stepping, this decentering of the gaze, this gap suggested by a work of art that renders a work necessary.

How does one represent his own time?…

Certainly it is not a pseudo-revolutionary art that can document it. One such horizon of expectation, normally the fruit of artifice and external to us, is the employment of predictable, prefabricated artifacts or products of circumstance. “Art counts for nothing,” when it is carried by the market, reviewed by critics with allegiances, and desired by collectors with diminished foresight, yielding nothing but itself and speculation—a framework of some interest, but it says nothing of our time. It brushes by us, gladly leaving humanity indifferent, passive, and bored by its vacuity.

At the opposite end of the spectrum we find Houda Ghorbel and Wadi Mhiri. “Obscurantism has injected bullets that smell of bloodied water into the roses of spring, leaving us an unfathomable future.” Indeed our shared space, with the Mediterranean on either shore, is experiencing dark times with the propagation of violence and hate. Attacks, suppressions, recessions—the cycle is locked and we run the risk of remaining ensnared indefinitely.

But what is there after the disaster?

The persistent dream is not suppressed. Consenting to the disaster is a method of perpetuating it. To face it head on, defying it and drawing it—as Goya once did in creating his “disasters of war”—is anything but a celebration of it. This is what Houda Ghorbel and Wadi Mhiri seek to accomplish in their own way, on their own terms.

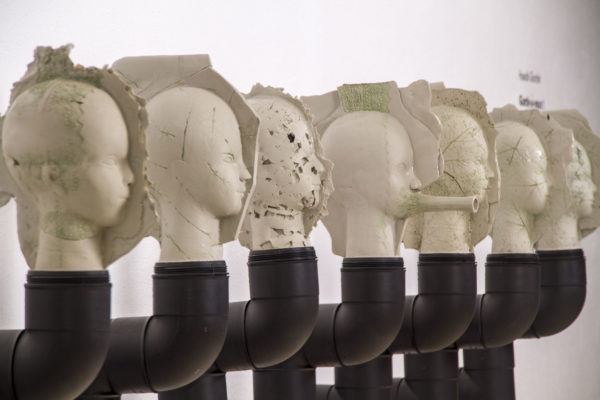

They justly represent their moment in time, lending it a face that is wounded, fractured, and stunned “Atten…tion!” the command rings forth. Be at the ready… or stand up straight, obedient, ready to march in step. One, two, one, two, one, two: the words collide somewhere between a military command and a single-track or binary thought. Seven heads, crafted by Houda Ghorbel, hang on the wall and look at us, awakening and disturbing us. They are traversed by a plane that bisects the hemispheres of the brain; the profiles are exposed and mutilated. Two faces share the same head, as if the world has irreparably divided us. The mask distantly inherited from statues of antiquity—almost featureless, harmonious, modeled with finesse—is only one part of the head, while the other is eroded by time, shapelessness, and a world that is coming undone before our very eyes. It is an opaque mirror to the face’s other half as it calls to the unknown, never to see what comes out of the other side. Why ignore or obscure the other half of the world? It is there and it lives in our heads, though it remains buried by obscurity.

“Atten…tion!” Yes, hold yourself at the ready. Do not allow yourself to be taken by events, nor by this separation that threatens us, nor by the lobotomy that slices the final hopes left in the depth of our unconscious.

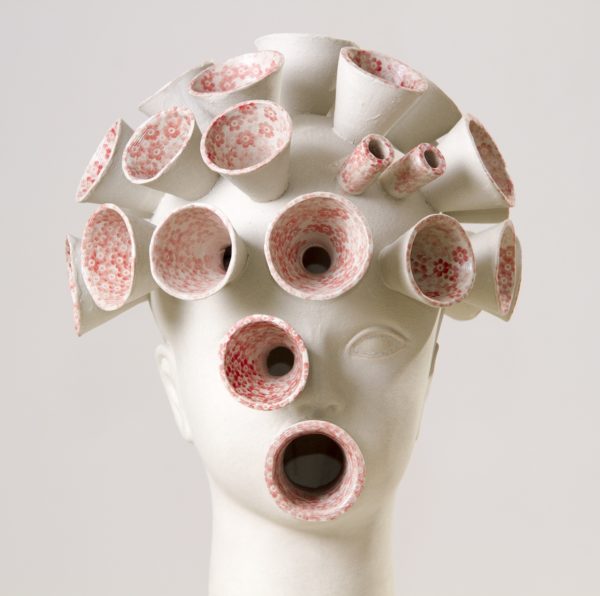

It is true that our thoughts are “channeled”… The installation of Houda Ghorbel, by means of pipelines surmounted by heads, creates a reflection on her command: “Beware!” We no longer belong to ourselves. Large machineries—the desirous machines already revealed by Deleuze and Guattari—fabricate our imagination and place us on rails, a path from which it is quite difficult to deviate. Violence circulates, irrigating our stupefied gaze with countless head-on, brutal, senseless images. We are connected to the pipelines of the world and all its refuse is being slowly deposited into our studded and bruised heads. Its agape mouth, silenced, no longer articulates words, but cries and wheezes; it has become like the world’s rectum which has replaced the lips that no longer speak. We have become merely pipelines and heads, nothing more than these connections that affect us, mold us, and leave us inhuman, here on the edge of the world.

‘Beware to those who would allow themselves to be channeled’ seems to be the message from the artist’s hands as they sculpt in response to our time.

“Sex, the bloodline, and death—all oppose the legacy of the world’s nobility,” André Malraux once observed while meditating on the role of art and creation when compared to our sad passions and obsessions.

Wadi Mhiri chooses a head-on approach by employing firearm cartridges and artillery shells and repositioning them before the viewer as if they were objects from our daily life. “Jihad al-nikah,” the senseless practice of sexual jihad, is “an agreement of voluntary submission” in the name of a supposedly sacred command that supports combatants. More often than not, it evolves into predatory acts on women who are abducted and treated like cattle. For instance, consider the Yazidi women who were taken and raped in Iraq by these rutting desperados who consider themselves to be a new kind of hero. Beneath the masks and headscarves lies a bed and cartridges, face to face, and nothing more. Love as a pistol to the temple!

What a decline from the poetic figures of love inherited from Islam, like The Ring of the Dove by Ibn Hazm. This story was later reinvented and filmed by director Nacer Khémir who opened our perception to all the beauty and delicacy of lovers. Today we are far from this state, with our “Jihad al-nikah”: a hymn to brutality and the possession of prey, to the piercing of bullets. A hymn to the slitting of throats in broad daylight on the street for a woman having offered her breast to the infant. Unfortunately, such accounts abound in Syria, Iraq, and other regions of the Arab world today.

How does one represent his own time?…

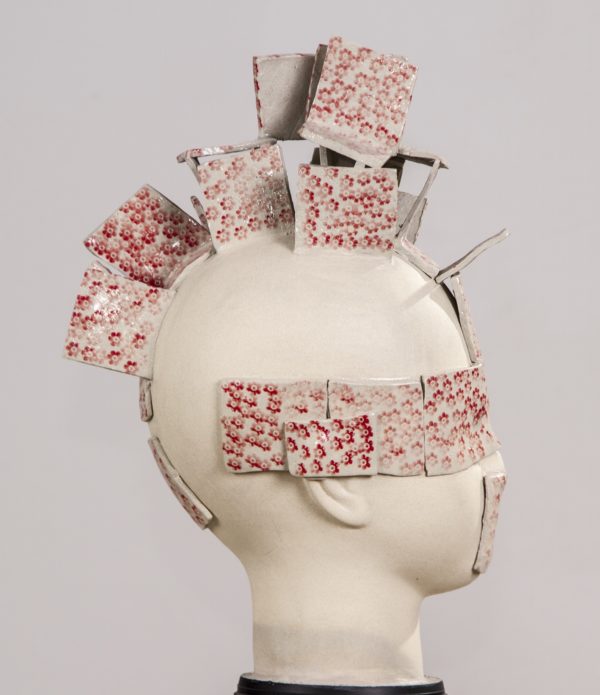

Reimagined cartridges and shells function as a sundial for “Les cinq moments de la journée” (“The five moments of the day”), another installation by Wadi Mhiri. Profane, perverted, and explosive, these prayers recreate the rhythm of an impious combatant’s day, a man fascinated by war. The artillery shells, ironic and obscene, return our gaze, forming a new sundial for a world that no longer truly turns correctly. How can we escape the influence of this shadow? We escape by liberty of thought or, more fittingly, by humor and laughter, by duty to insolence, or even irreverence, in the face of such blindness.

Wadi Mhiri has the tender sensibility to present these shells and cartridges to us by placing them in a scene that emphasizes the banality of evil, and without the possibility of averting our eyes or acting as if we cannot see them. No, no—these shells are there, but they have been decorated with blue flowers and have become desirable oblong forms, almost ridiculous in their flirtation with kitsch. These shells/objects, originally formed by the French soldiers of World War I, have been transformed into vases for cut flowers.

“Le bleu du mal” (“The Blue of Evil”) is an installation that presents a series of seven shells placed on a white pedestal with a countdown timer, giving the viewer a sense of explosive sweetness. These painted objects seem harmless but the countdown has begun and will not stop. Does it lead to one final explosion?

But what is there after the disaster?

Is it the heaven of the afterlife, or the great nothing, or a merry apocalypse? Who can pretend to know?

On our path in these troubled times, a few glimmering breaks in the cloud remain, along with some works of art that speak to us, including those by Houda Ghorbel and Wadi Mhiri.”

Text written by Thierry Fabre and Translated by Joseph L. Underwood